Saint Moninne of Killeavey was one of Ireland’s earliest female saints and lived in the years 435 – 517. SHe was the daughter of a king, Machta, whose lands stretched from modern-day Louth through to Armagh. Her mother, Comwi, was also from royalty, her father being a northern king. When Patrick travelled through Machta’s territory, he met the king and subsequently baptised their daughter, giving her the name of Patrick’s sister, Daraerca. He prophesied that the girl would be always be remembered. Daraerca was also known as both Moninne and Blínne, so the people had plenty of titles to choose from.

Moninne is said to have funded a monastery of nuns at Faughart, where Bríghid is originally thought to have come from, as well as anumber of convents in both Scotland and England. She is then recorded as having moved to modern-day County Wexford to live under the direction of St Ibar, before returning home to the slopes of Slieve Gullion where she founded her church and religious community. They lived a life of vigorous instruction, initially consisting of eight virgins and a widow with a baby at Killeavy in what became, under the later colonial administration, County Armagh.

On the northern side of Killeavy Old Church, there is a large granite slab measuring approximately seven feet long, five feet wide and one and half feet thick. This is suppoedly the grave slab for St Moninne. It was here that religious ceremonies were conducted in the past, before pilgirms continued up the side of the mountain to a beautiful holy well dedicated to the saint, with an accompanying prayer tree. Her feast day is 6th July.

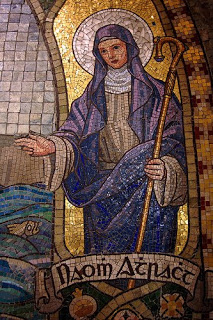

St Moninne’s Church, KIlleavy

Saint Trea of Ardtrea

St. Bríghid of Ireland, also spelled Brigid, Brigit or Bridget, also called Bríghid of Kildare or Bride (Irish Bríd or Bríghid). Bríghid is the best known of the female Irish saints. She was born in Faughart, on the border just outside Dundalk and is said to have died c. 525 in County Kildare. Her feast day is February 1. She was an Abbess of Kildare and is one of the patron saints of Ireland.

There is a some suggestion that as Bríghid has the same name as a formidable pagan goddess, as well as the same feast day, she may not have existed at all. However, it appears more likely that, as a Christian figure, over time Bríghid from Faughart merely subsumed the pagan figure into her own legend, as was the habit with Christianity across the globe.

Many readers will no doubt remember learning how to make St Bríghid’s crosses, from reeds, at school. I recall the great sense of satisfaction when I managed to produce a St Bríghid’s cross that didn’t fall to pieces immediately. Sadly, I believe that this ancient tradition is no longer as widespread as it once was.

Today, there is a shrine and small, modern church building at Faughart in her memory. There is also an ancient ruins of a church building at nearby Faughart graveyard. It is the burial place of Edward Bruce, brother of Robert (of Braveheart fame), who was declared High King of Ireland when he arrived with his Gallowglasses to try to free Ireland from the English presence. He died in the Battle of Faughart 14th October, 1318.

There is a holy well and prayer tree, both still in use, at Faughart graveyard.

Eithne and her sister Sodelb are two relatively obscure Irish saints from Leinster who are supposed to have flourished in the 6th century. They are commemorated together on 29th March, though 2nd and 15th January were also marked out as feast-days.

Saint Buriana (or Berriona, Beriana or Beryan) was a 6th-century Irish saint. She was reputed to have been a hermit in St Buryan, near Penzance in Cornwall. She has been identified with the Irish Saint Bruinsech.

She is said to have been the daughter of an Irish king, and travelled to Cornwall from Ireland as a missionary to convert the local people to Christianity. According to the Exeter Calendar of Martyrology, Buriana was the daughter of a Munster chieftain. One legend tells how she cured the paralysed son of King Geraint of Dumnonia. Buriana ministered from a chapel on the site of the current parish church at St Buryan.

Buriana’s feast day is 1 May.

Saint Breage or Breaca (with many variant spellings) is another Irish saint venerated in Cornwall. According to her late hagiography, she was an Irish nun of the 5th or 6th century who founded a church in Cornwall. The village and civil parish of Breage in Cornwall are named after her, and the local Breage Parish Church is dedicated to her. A Breage Fair is held on the third Monday in June.

Sait Athracht (Modern Irish Naomh Adhracht), in Latin sources Attracta, is the patron saint of the parish of Locha Techet (Lough Gara) and Tourlestrane, County Sligo. Her feast day is August 11.

A native of County Sligo, she resolved to devote herself to God, but being opposed by her parents, fled to South Connacht. She is said to have made her first foundation at Drumconnell, near Boyle, County Roscommon, from whence she removed to Greagraighe or Coolavin, County Sligo.

Her legend states that she took her vows as a nun under Saint Patrick at Coolavin. She then moved to Lough Gara, where she founded a hostel for travellers at a place now called Killaraght in her honor. The hostel survived until 1539.

She lived in the sixth century, and had a brother named of St Connell, who is associated with Conainne. Local tradition remembers her great healing powers. Her convents were famous for hospitality and charity to the poor. It would be hoped that all Sligo hotels and B&B’s would keep their prices low as a mark of respect to St. Athracht…

Saint Athracht

What we can see from this incomplete list is that Irish female saints are almost entirely confined to the early medieval period. They are all contemporaries, not only of one another, but also of St Patrick. It would appear that after this time the growing misogyny within the Church, which was imported from both England and the continent, became so virulent as to reduce all women to a second-class status.

It is unfortunate that the male-dominated institution succeeded in sidelining women in this way, as Patrick seemed to have no objection to the presence of strong and determined women within his religious community. But then again, Jesus of Nazareth also did not discriminate against women and is said to have treated them as equals to the men among his disciples.

In Ireland, the pre-Christian pagan people had long revered female deities such as Callí, Badbh, Macha (from which comes Ard Mhaca or Armagh), Danu, Brigid, Clíodhna, the Morrigú (goddess of death who often appeared as a raven, and is said to have sat on the shoulder of the dying Cúchulainn) and Áine to name but a few.

After the gradual victory of Christianity over the pagan faiths, the native people still sought to worship female characters, and so we can see how there was an early reverence for the saintly women listed above. Marian worship, or the celebration of the Virgin Mary, is also extremely strong in Ireland. Perhaps this is an indication that although Christianity has been in our land for almost 1600 years now, it has not entirely displaced the earliest non-Christian beliefs that were followed for more than 7000 years.

Across Ireland, there is still the tradition of the ‘cure’ (not the ‘hair of the dog’ type), whereby certain individuals are said to have been gifted with the ability to heal specific ailments. This has been passed down from the pagan shamanic traditions of ancient Ireland.

Christian holy wells were once pagan holy wells. Christian prayer trees were once used by pagans to petition their deities. Christians of today tie rags to such trees and make either a wish or say a prayer, just as the ancient pagans of Ireland did.

Cranfield holy well and prayer tree, County Antrim

Tossing coins into a fountain and making a wish is a pagan tradition of votive offering to the gods of the underworld, common across time and culture in our world.

Travel the country roads of Ireland and you will see ‘fairy trees’ and ‘fairy mounds’ still standing alone in fields, untouched by those who respect the ancient history of our people.The pagans had great reverence for such sites and the blackthorn and hawthorn that often grew there.

Ancient Ireland had a great many powerful and formidable women. These saintly ambassadors were accepted within their communities as natural leaders. They built and taught and guided. They were a sign of how the people of Ireland always regarded the women here. In later times, as the role of the females of our nation became diminished due to outside malign influence, the ordinary people were still inclined to turn to saintly female figures for help and guidance.

It has taken many centuries for the male stranglehold on society to become weakened (although not yet gone). Today, Irish women are once again able to better assert themselves in their communities, as they did so easily 1500 years ago.

It is true that old habits are hard to break, and the tradition of the strong and beautiful, yet kindly, woman in Ireland is deeply interwoven into the fabric of our identity.

Could it therefore be, that if you were to scratch the surface of any Irish person, even – and perhaps most especially – those who revere our female saints, you would uncover the pagan beneath?